In Rwanda, Suicides Haunt Search for Justice and Closure

By Craig Timberg

By Craig TimbergWashington Post

Foreign Service

Friday, February 17, 2006;

Page A01

Jeanviere Nzamwitakuze, 31, was widowed by one of 69 suspected perpetrators of genocide who have killed themselves rather than face the public in traditional courts.

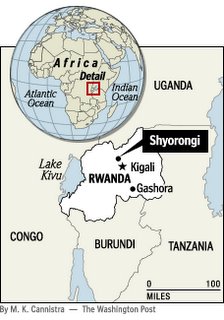

SHYORONGI, Rwanda -- In the years after the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Innocent Mulinda, 39, started a family, tended to his red-earth farm and won a local election for a government job. Rumors that he had participated in a murderous militia in this hillside town seemed behind him.

But that changed with sudden vengeance last April, witnesses said, when a confessed militia member told a traditional, open-air court that Mulinda was not merely a fellow militiaman but a leader who carried an AK-47, manned roadblocks and exhorted others to kill.

Hours after the testimony, when darkness had fallen across his neighborhood of mud-walled homes, Mulinda drank a bottle of pesticide. He would leave behind a wife, two young sons and oddly conflicted feelings among Rwandans longing for tidy justice with a full confession and a punishment befitting his crimes.

Mulinda's agonizing death, which his wife said took more than two days, was among a rash of suicides and attempted suicides that Rwandan officials have recorded in the past year among genocide suspects as traditional courts have begun to hear cases. Between March and the end of December, 69 suspects killed themselves and 44 others tried to. Many others attempted or committed suicide, officials say, in the months before record-keeping began.

It is not clear what motivated the suicides -- belated guilt, shame, fear of prison or fear of exposing friends who also participated in the 100-day ethnic slaughter, in which most of the 800,000 victims were hacked to death with machetes or beaten to death with clubs.

And though survivors express little sympathy for participants who killed themselves more than a decade later, some say their hopes for closure -- a full public accounting of crimes and accomplices, as well as details about the victims' final hours -- have been dashed by the suicides.

"No person has the right to punish themselves," said Benoit Kaboyi, executive secretary of Rwanda's largest association of genocide survivors. "They have to suffer for what they have done."

Rwanda's 8 million people are jammed into a country smaller than Maryland, making it one of the world's most densely settled agrarian societies. In many places, nearly every patch of reddish earth is cultivated in a patchwork of fields that stretch up, and often over, Rwanda's countless hills.

Many of the killings happened as ethnic Hutu militias rampaged through steep hillside villages in search of Tutsis, a minority ethnic group, or those who sought to defend them. In Shyorongi, a roadside market town about 12 miles north of the capital, Kigali, militias killed an estimated 6,000 people -- more people than there are residents today.

Those accused of organizing and inciting the genocide are being tried at an international tribunal in neighboring Tanzania. Rwanda's overburdened criminal justice system is handling allegations of murder and rape.

Mulinda's case was handled by one of the more than 12,000 traditional courts, called g acaca for "under the tree," where ordinary citizens are trying, convicting and setting punishments for those accused of such lesser crimes as looting and being indirectly involved in deaths.

These courts cannot hand down the death penalty but can sentence perpetrators to lengthy prison sentences or community service, and order that restitution be paid to victims. They also can refer cases of rape and murder to the criminal justice system if clear evidence emerges.

The gacaca courts are expected to hear at least 100,000 cases. But officials say that number could reach 500,000 as the first round of defendants -- many of them former prisoners freed in exchange for pleading guilty -- implicate others in their testimony.

Gacaca officials, who began tracking the suicides in March after an initial round of cases in January and February last year, have documented the horrors: An elderly man drowned himself in Lake Kivu, on Rwanda's western border, on the day he was accused of killing several of his grandchildren. A 28-year-old man, the last surviving member of his family, killed himself after being accused of raping his Tutsi mother, according to gacaca officials.

"Sometimes we discover a situation we cannot understand ourselves," said the court's executive secretary, Domitilla Mukantaganzwa. "We are praying for our nation."

In Gashora, about 30 miles east of Kigali, Sylvester Ngiriyambonye, 56, returned home in 2003 after spending years in Rwanda's notoriously grim, crowded prisons for his role in the death of a Tutsi woman and her teenage daughter.

Two years later, a government official visited Gashora to begin organizing the gacaca court where, under the rules of Ngiriyambonye's guilty plea, he would have been forced to testify against other militia members. Instead, his widow said, he hanged himself from a tree.

In nearby Lirima, Charles Rubuga, 67, was accused last April of killing a man at a roadblock. He denied the charges over three days of gacaca hearings, family members said.

"He came back a changed man," said his widow, Angelina Ntibanoga, 65, who had been married to Rubuga for 45 years.

"All these years we've lived together, I have never assaulted anybody," she recalled him saying despondently. "I have never killed anybody. And now they have accused me of killing."

The next morning, she said, Rubuga walked several miles to the crocodile-infested Nyabarongo River, removed his clothes, laid down his machete and hurled himself in.

Whatever their alleged crimes during the genocide, those who have committed suicide have ripped an unexpected hole in the lives of the friends and family members left behind.

In Shyorongi, Jeanviere Nzamwitakuze, 31, married Mulinda the year after the genocide. She had heard rumors of his involvement but said she believed his account of being only a low-ranking militia member who never killed anybody.

Now she must tend to the family's crop of beans, corn and peas by herself, as well as raise their sons. His decision to leave them behind has caused her great sadness and turmoil, she said, though she maintained it was the pain of a boil on his leg that caused him to kill himself, not anguish over the accusations.

"There are so many people accused of the same thing, and they are still living," she said, averting her teary eyes.

The man who accused Mulinda of participating in the genocide, Canisous Munyeraraba, 36, a fellow militia member, implicated more than a dozen others. For confessing to illegal possession of a gun and looting, Munyeraraba was released from jail, at least temporarily, and will eventually receive a reduced sentence.

Munyeraraba said the torment of confronting their own horrendous crimes is more than some men can bear. He said Mulinda had been a gentle, honorable man, both before and after his alleged crimes.

"Many people changed during the genocide," Munyeraraba said. Mulinda "was not a violent person. He just found himself in the atrocities, like many others."

Others were less ready to excuse what Mulinda had apparently done. Beatrice Mukamusoni, 41, a tall, lean Tutsi, did not see Mulinda commit any crimes because she fled Shyorongi in the early days of the killing, she said. But Mukamusoni, whose husband, parents, sister and eldest child were killed in the genocide, said she had long heard rumors that he was a leader within his neighborhood militia.

"All these people who had a role, they should resolve their cases by committing suicide," she said, without a trace of remorse.

But her emotions about Mulinda's death were more complex. She had respected his work as a government official in recent years, and she said they enjoyed an amicable relationship. Such things are not uncommon in post-genocide Rwanda, where killers and survivors have returned home to the same villages, often living side by side.

On hearing the news of Mulinda's suicide, she said, she felt only sadness.

"If he's not innocent, that means many other people around us are not innocent," she said. "So shall we live in this country alone?"

Special correspondent Silver Bugingo contributed to this report.

Washington Post, United States - Feb 16, 2006SHYORONGI, Rwanda -- In the years since the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Innocent Mulinda, 39, started a family, tended to his red-earthen farm and won a local ...

Houston Chronicle, United States - 2 hours agoBy CRAIG TIMBERG. SHYORONGI, RWANDA - In the years after the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Innocent Mulinda, 39, started a family, tended ...

MSNBC - Feb 16, 2006By Craig Timberg. SHYORONGI, Rwanda - In the years since the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Innocent Mulinda, 39, started a family, tended ...

--

« Mbwire gito canje, gito c'uwundi cumvireho» ("Conseils à mon sot, de sorte que le sot d'autrui en profite", Paul MIREREKANO, janvier 1961).

"The greatest thing in this world," said U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., "is not so much where we are, but in what direction we are moving."

"It is not truth that makes man great; but man that makes truth great." (Confucius)

1 Comments:

هل تريد شراء افضل اثاث مكتبي معارض اثاث مكتبي يوجد العديد من معارض الأثاث المكتبي في مصر، يمكنك الذهاب إلى أي معرض في القاهرة وتجربة أشهر معارض أثاث المكاتب في القاهرة - Starwood للأثاث المكتبي.

Post a Comment

<< Home